By David Gill, reprinted from The 313.

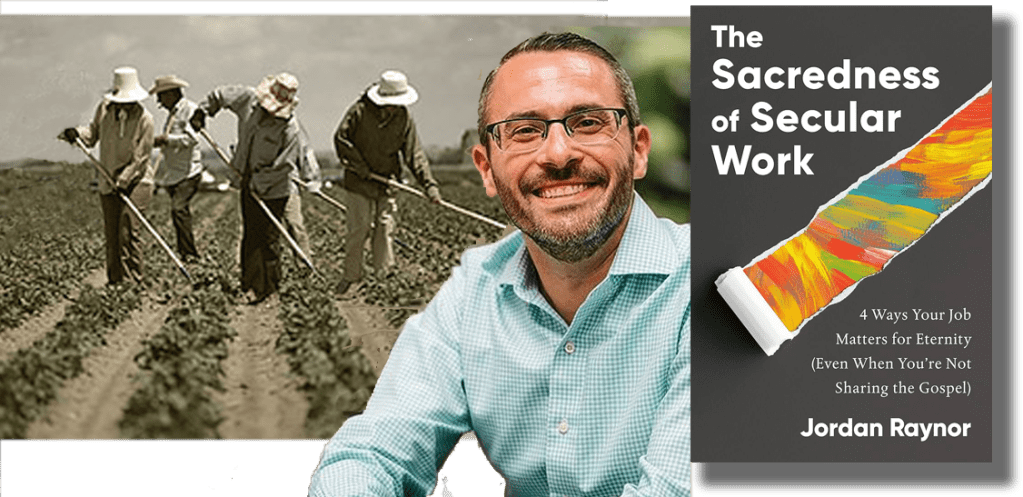

According to his website (www.jordanraynor.com), Jordan Raynor is “a leading voice of the faith and work movement. Through his bestselling books (The Sacredness of Secular Work, Redeeming Your Time, The Creator in You, etc.), the Mere Christians podcast, and his weekly devotionals, Jordan has helped millions of Christians in every country on earth connect the gospel to their work. In addition to his writing, Jordan serves as the Executive Chairman of Threshold 360, a venture-backed tech startup which Jordan previously ran as CEO following a string of successful ventures of his own. Jordan has twice been selected as a Google Fellow and served in The White House under President George W. Bush. A sixth-generation Floridian, Jordan lives in Tampa with his wife and their three young daughters. The Raynors are proud members of The Church at Odessa.”

Wow! Busy guy. “Millions in every country on earth”! Raynor’s energy and enthusiasm come through his breezy, positive writing from cover to cover. As the book’s subtitle suggests, a major part of his message is to counter any idea that personal evangelism (seeking conversions) is the sole purpose of Christians going to work. The first half of The Sacredness of Secular Work is a critique of the “abridged Gospel” and “half truths about heaven.” That “abridged Gospel” limits it to “the good news that Jesus came to save people from their sins.” Of course, that is Gospel/good news but it leaves out the broader message of the all-embracing kingdom of God/heaven which encompasses all of creation, all of our life (including our work), now and forever. From creation to eternity God is at work and we are called to participate in that work. The “half truths about heaven” limit the afterlife to an escape from a fallen world into an endless worship service. Raynor does a nice job of showing how sanctified (by God) human work is part of the “glory of the nations” brought into the New Jerusalem (echoing studies by Darrell Cosden and N.T. Wright among others).

In Part Two, Raynor develops “four ways your job matters for eternity.” First, it “contributes to God’s pleasure” as it obeys God’s commands, pursues excellence, brings us joy and pleasure, and participates in God’s work with a sense of wonder. Second, it promises eternal rewards for faithful work and may even “last physically into heaven.” The promise of eternal rewards is to those who work hard, endure difficulty, give to the poor, pray, do good to enemies, and offer generous hospitality. Our faithfulness may not bring great reward in our lifetime (no prosperity Gospel heresy here!) but we work with confidence in God’s promises. Third, we “yank pieces of heaven onto earth” in finding ways to live out now the reality of God’s coming kingdom. We don’t just wait for that promised kingdom but live it out now. Raynor doesn’t reference it but Paul argues the same in Romans 13:11-14 when he says we are still living “in the night” but should behave “as in the coming day.” Finally, fourth, Raynor gives good counsel on “how to make disciples without leaving tracts in the break room”—effective strategies for sharing our faith in a post-Christian context.

Raynor’s writing bristles with an infectious energy, passion, and humor. He is great at using illustrations from history and pop culture. He draws on solid resources (Tim Keller, Katherine Leary Alsdorf, Amy Sherman, Darrell Cosden, N.T. Wright, and many others). He ranges widely, deeply, and convincingly through the life of Christ and the teaching of Scripture from Genesis to Revelation. Raynor inveighs against an “instrumental” reduction of work as something only valuable as a means to the end of converting others so they can be saved for heaven. Work, he says, has “intrinsic” value, i.e, good in itself not just in its effectiveness for ends beyond itself (like successful evangelism). With that said, much of his argument remains of an instrumental character: we work for heavenly rewards.

Raynor does provide some specific and concrete lists of what kingdom work looks like as creation and redemption hit the ground in our workplace presence and activity—without very fully or rigorously developing an understanding of the work of God as creator, sustainer, wisdom-giver, justice-advocate, and redeemer (in its various dimensions). His definitions (work, disciple, etc.) are not always as precise as I wished. He doesn’t emphasize enough the essential “partnership” aspect of biblical teaching on work and discipleship; still a bit too individualistic. But these are the quibbles of a (new) fan and I recommend whole-heartedly The Sacredness of Secular Work to veterans as well as newcomers to the faith and work movement. It will motivate many readers and get them started on the exciting journey of workplace discipleship.