By David Gill, reprinted from Workplace 313.

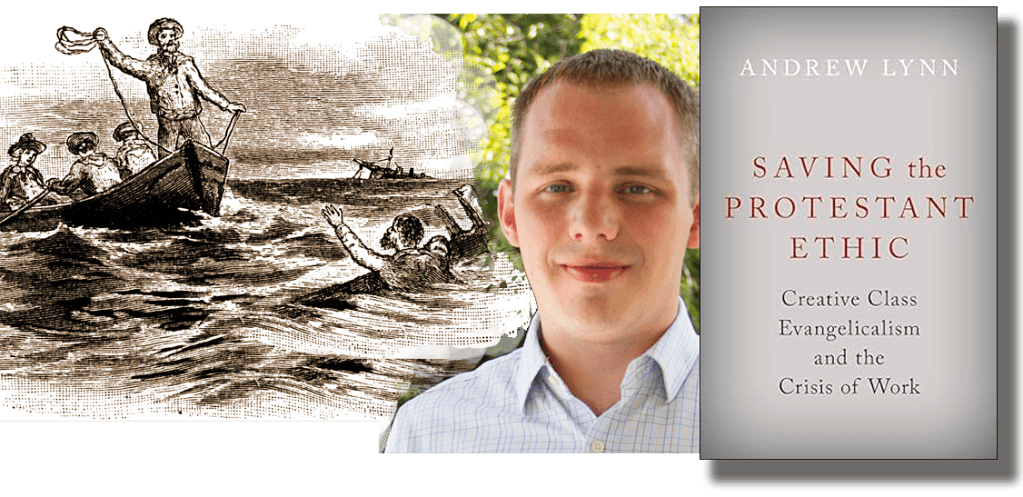

Andrew Lynn is

a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Virginia Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture. Andrew earned his BA in political science from the University of Notre Dame and his MA and PhD in sociology from the University of Virginia. His dissertation—which eventually led to this book—was directed by UVa Professor James Davison Hunter, widely published and respected sociologist of religion and culture and author of To Change the World: The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World (2010).

Lynn’s title, Saving the Protestant Ethic, does not fully capture the scope or importance of his book. For sure, Lynn draws heavily and respectfully on 19th century sociologist Max Weber’s Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism and other works but the range of his sources is really astonishing: Luther, Calvin, Wesley, the Puritans, the 19th century revivalists like Moody, dispensationalists like Darby, social gospel leaders like Walter Rauschenbusch, Keswick-style inner-life leaders, 20th century Fundamentalists and the Evangelical leaders like Carl Henry and Billy Graham—and a veritable host of lesser-known speakers and writers. What did they think and write about Christianity in relation to work and/or economics? Lynn has done us all a great service in describing not just the individuals but the broader movements, trends, and impacts from the 16th to 21st centuries.

Princeton’s David W. Miller’s 2007 book, God at Work: The History and Promise of the Faith at Work Movement, has, to this point, been the standard, widely-appreciated account of the movement. Lynn’s treatment is now the new standard, not just bringing the story up to date but ranging more widely and deeply over the centuries. Two hundred and fifty pages of text are followed by one hundred pages of notes and indices. Beyond his broad review of faith, work, and economics literature, Lynn attended many faith at work events and interviewed dozens of leaders he chose—based mostly on their frequency of speaking at conferences. Even after my own sixty-year immersion in this topic I felt like I leaned something new on every page.

Lynn’s work is in the style of American sociology—lots of emphasis on book sales, event attendance and demographics, and so on—whatever can be counted. But he is at the same time an insightful analyst of this data, developing categories and offering suggestions about causes, linkages, and impacts. He is mostly descriptive and detached but ends with some cautions and hopes.

Here are some of the broad takeaways:

- Luther and Calvin had major and enduring impact with their recognition of all workers as servants of God equally as important as pastors, priests, and clergy.

- The dispensationalism of Darby and his followers (represented in the Schofield reference Bible and more recently Hal Lindsey and Tim LaHaye), along with the evangelism of Billy Graham and others—focused on saving individual souls for the afterlife—leaves the world of ordinary work mostly as a matter of necessity and as a means of funding missionaries and religious work.

- The Keswick-style emphasis on spirituality, the devotional life, and the Holy Spirit tended to move the focus away from work to the individual’s inner life. At best it counseled having a good attitude at work, no matter what that work was.

- The emphases on “all work equally is God’s work” and “you are where God has placed you” have tended to undermine any biblical critique of unethical work and of businesses and economies that fall short of biblical ethics. Work may only have utilitarian value as a school of Christian character (patience, endurance, attitude) and an economic necessity.

- The “God-promises-everyone-wealth-and-success” Prosperity Gospel has captured the thinking of many pastors and individual workers. In a more general trend faith and work funders and leaders tend to be successful business leaders (with their think tanks and foundations)—funding an idolatry of money, wealth, and worldly success, and cutting the nerve on corporate or political, institutional and systemic reforms. Many of the loudest voices protest what they see as socialism and intrusive government regulation. Little criticism is made of monopolistic capitalism and its “invisible hand,” which, for them, is essentially the hand of God.

- The “dominionist” and “reconstructionist” movements going back to Dutch leader Abraham Kuyper put the focus on claiming and achieving power over all sectors of life (rather than “salting” and serving “from below” or within), ignoring the downsides of such a strategy

- Most of the leading figures of the faith at work movement have been highly-educated white men. Women and non-white speakers, writers, and leaders are few in number—and even those rare exceptions often represent the same economic convictions as their white male counterparts. (Personal note: the only place my voice is included is in his unattributed quotation of a line from my plenary speech that opened the 2016 Faith at Work Summit—“The contemporary faith at work movement remains ‘Too male and too pale’”).

- Lacking a robust interest in workplace and economic ethics, the movement may well degenerate into a mere handmaiden of the existing economy, effective only in shaping compliant followers into hard-working cogs in the existing world of work.

- Going forward it is critical that, while “work matters to God,” Christians must resist centering their identity on their work and, rather, cultivate their identity as followers of Christ and members of faith communities. “Saving the Protestant work ethic” would mean not losing our primary religious identity in which work can find its fundamental purpose and the specific ethical values it entails.

I think Lynn is mostly (and regrettably) correct in his description and analysis. One of his observations is certainly correct: today’s faith at work movement “had no single origin—and certainly no single mastermind behind it” (p. 106). I need to point out, however, that as broad-ranging as Lynn’s research was, it only captures what he was looking for. Fair enough and immensely helpful, but it leaves out the Black Church history of holistic discipleship, community, and social/economic witness from which we can learn so much. While only Katherine Leary Alsdorf, Amy Sherman, and (earlier) Dorothy Sayers get quoted (and praised) a lot, the huge uptick in the past decade of women’s written and organizational contributions to faith and work need also to be noted. There is next to no attention to entrepreneurship (creating jobs and work), especially at the grass roots level (not just high tech and big investor enterprise). If that isn’t faith at work, what is? While wealth and economic philosophy play large, there is no attention to the way technology (not just the tools and devices but the philosophy and values) has been radically changing the workplace, representing a potential idolatry the equal of Mammon. The privileging of financially successful, popular voices in the movement means missing out on a vast reality under that radar.

Those of us called to encourage faithful, biblical workplace discipleship have work to do—appreciatively building on the foundation of our forebears for sure, but driving deeper into Scripture itself, the true source of any faithful movement. Our calling is not to seek the power and authority to bulldoze the workplace and economy but to be the biblical “salt” and “light” of that arena.

As I hope you can see, I believe Andrew Lynn’s study is an invaluable contribution, essential reading and discussion, inviting and stimulating an improved faith at work movement.