By David Gill, reprinted from The 313.

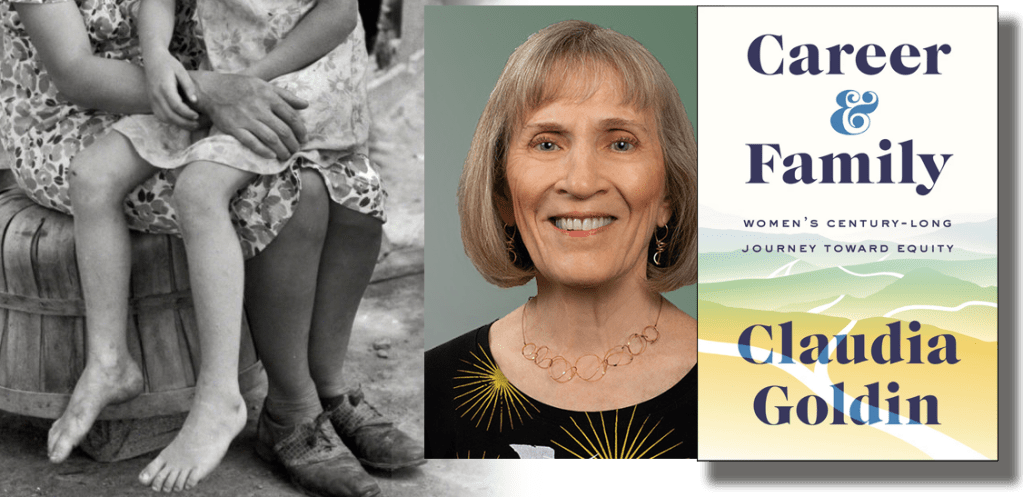

Claudia Goldin, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics at Harvard University, was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2023 for her research on the history of women in the labor market. Her most recent book, Career & Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity (2021), summarizes her findings. An economic historian and labor economist, Goldin is the author or co-author of several books on a wide range of topics, including the female labor force, the gender gap in earnings, income inequality, technological change, education, and immigration. Those books include Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women (1990), The Regulated Economy: A Historical Approach to Political Economy (1994), The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century (1998), Corruption and Reform: Lessons from America’s Economic History (2006), The Race between Education and Technology (2008), and Women Working Longer: Increased Employment at Older Ages (2018).

Career and Family is an economic and sociological study of American women’s quest for both career and family since roughly 1900 to the present. She summarizes five successive chronological phases of that journey with the labels “Family or Career,” “Job then Family,” “Family then Job,” “Career then Family,” and “Career and Family.” Goldin makes a distinction between “job” (often just for basic needs, often unskilled, temporary) and “career” (longer-term, often requiring significant education). Goldin absolutely buries her readers in statistics, graphs, and charts. I felt like she was saying “If it can’t be counted, it doesn’t count.” Her statistics show some correlations but this is not quite the same thing as revealing causation. Her statistics show behavior (e.g., receiving a degree, having a child) but rarely get at attitudes and intentions.

Over the past century, legal, cultural, and economic barriers have fallen (if not fully disappeared) that previously prevented or impeded women’s wishes for an education and career. At this stage, women equal or surpass men in college graduation rates in many fields. Laws now prohibit discrimination and mistreatment of women in the workplace. Birth control and reproductive technologies like IVF enable women to pursue careers and (mostly) schedule the arrival of children—rather than yielding to career-disrupting biological rhythms in one’s Twenties and Thirties. A century ago, it was a given that a woman with a college degree had to choose between having a career and a family. Today, many women want to have both a career and family. Much has changed but challenges remain.

Goldin shows how many professions are “greedy”—paying disproportionately more for long hours and weekend work, and how this perpetuates disparities between women and men if children are in the picture. Successful careers usually reward those who work long, extra hours and are on-call constantly—difficult requirements if one wants a successful family life. Goldin demonstrates how the era of COVID-19 sometimes hindered women’s advancement, but in other ways may have a silver lining because of the growth of remote and flexible work. Antidiscrimination laws, improved technology, less biased managers, and more progressive husbands willing to share responsibilities for both career and family are all important. Career and Family explains why we must make fundamental changes to the way we work and how we value caregiving if we are ever to achieve gender equality and couple equity.

Goldin could have paid more attention to parenting as a legitimate and honored “career” in itself. She gives a nod to the economic value of unsalaried parenting and household management but since this is difficult to quantify it doesn’t factor into her argument. The whole notion of career (or vocation or profession) is fundamental to this topic. Fair and humane compensation and working conditions are basic issues. Technology plays a much bigger role, especially as it replaces more and more job specialties. Goldin provides an interesting comparison between the legal and pharmaceutical professions. Law partnerships and practices still privilege those for whom career means long hours and 24/7 connectivity. Hence men dominate. Pharmacists today rarely work independently or for boutique offices; instead they mostly work designated hours for big corporate operations at CVS, Walgreens, WalMart etc.. Female pharmacists do as well financially as males; they find it easy to work limited or flexible hours with no financial or career-track penalties. But what has disappeared is personal, customized relationships with patients/clients. It is easy to see that as computer programs and AI take over more and more of legal practice, as individuality disappears and robotization takes over, a kind of equality and standardization will rise.

In short, Goldin’s research is admirable—Nobel Prize admirable—but it is mostly a description of the “disease,” highlighting its links to educational degrees, and offering little prescription for a “cure.” As a Christian ethicist, I am drawn back to the foundational biblical message that both child-rearing and field-labor are mandates given jointly and equally to men and women in partnership. I am drawn to the idea that our work (paid or unpaid, career-consistent or gig-shifting) is always about delivering good products and services out of love for God and our neighbors. I believe children need two parents not just to be conceived but to be cared for and raised. Every man and woman needs—in some significant way or another—to participate in both career and family. It’s part of what it means to be human. And these kinds of perspectives need to be added to Goldin’s input if we are to make progress.